Concussion in Sport: what did, or should, governing bodies have known?

1. INTRODUCTION

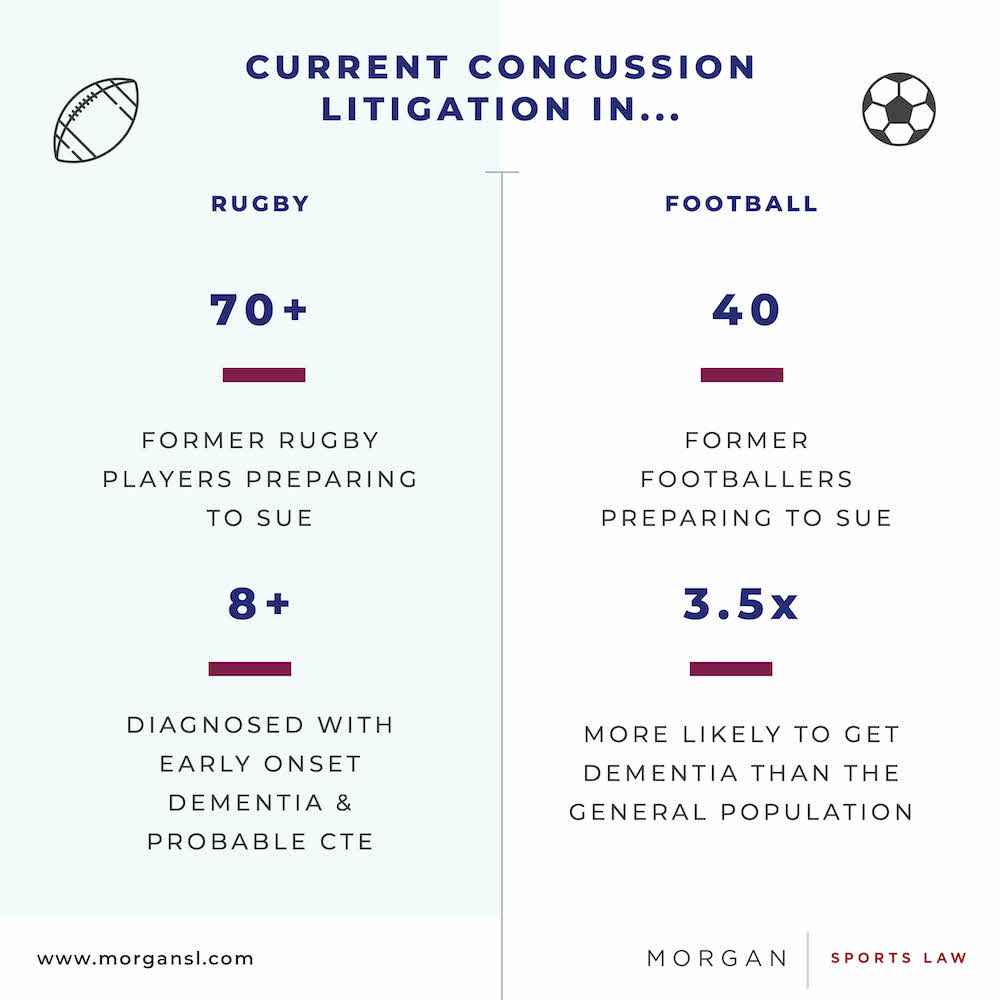

Group litigation is on the horizon for both rugby and football in the English courts. It has been widely reported that groups of former professional players are preparing to sue the sports’ governing bodies in respect of the long-term neurological conditions from which they are now suffering and which, they allege, were caused by the governing bodies’ negligence.

In rugby’s case, at least 70 former players are reportedly to sue, and at least eight of them have been diagnosed with early-onset dementia and probable chronic traumatic encephalopathy (“CTE”). They claim that this has been caused by the repeated concussive and sub-concussive blows they received during their rugby careers, and that rugby’s authorities should have done more to protect them.

Setting aside legal questions of causation and duty of care, much attention will be given to the issue of whether governing bodies adequately handled concussion and, particularly, the long-term risks associated with repetitive concussive and sub-concussive head trauma. From the perspective of the English law of negligence, the question will be whether the governing bodies acted reasonably in the circumstances. If they did not, they will be deemed to have been negligent and may thus be liable.

Crucial to the question of reasonableness will be the state of the scientific/medical understanding of repeated concussions and CTE – the devastating condition that the players allege has been caused – at the relevant times. Questions will be asked about what the governing bodies knew, and what they ought to have known. This article will consider how the understanding has evolved over the past century.

2. PUNCH-DRUNK SYNDROME

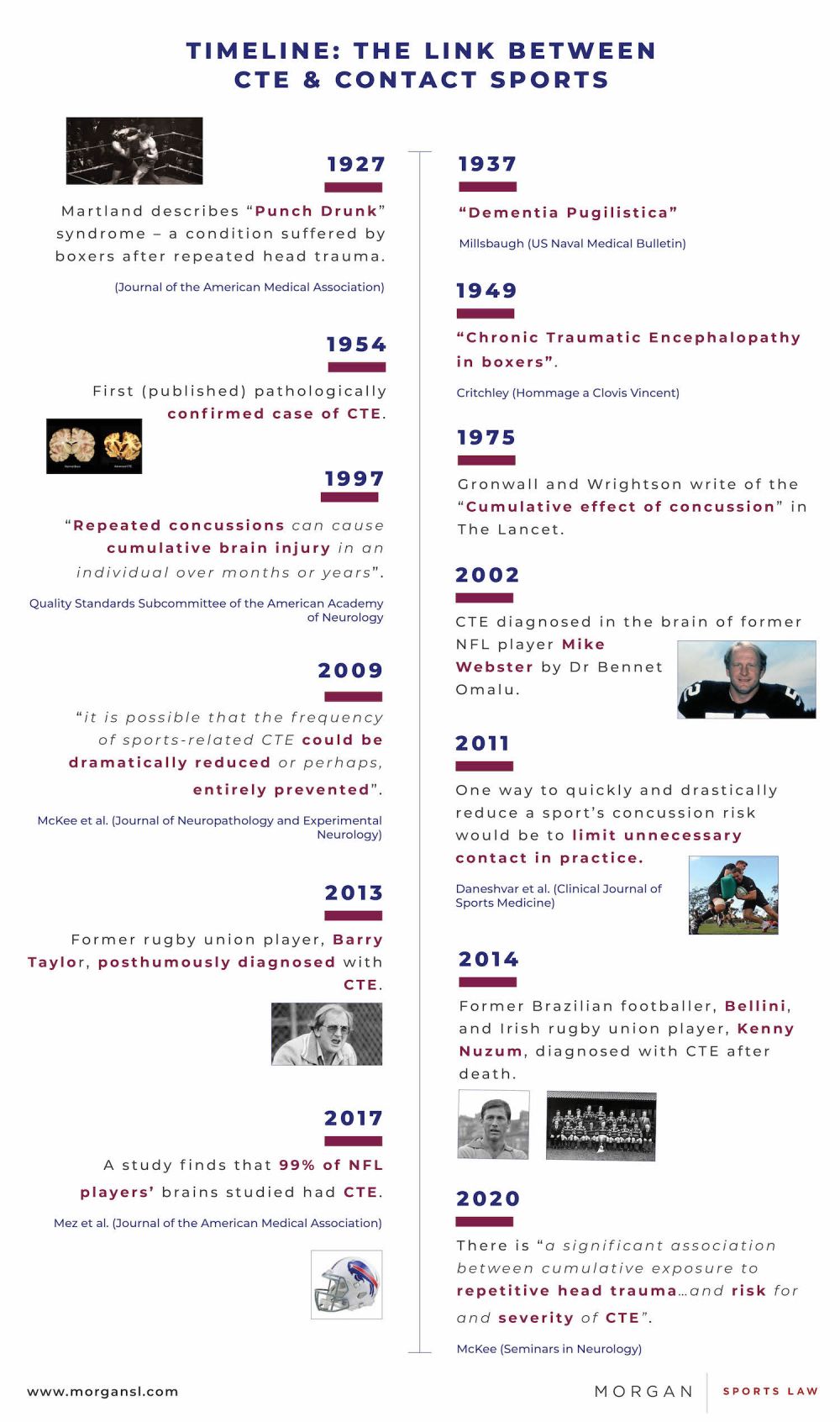

The first evidence of the long-term effects of concussion in the medical literature can be found in 1927, when Osnato and Giliberti found a “strong likelihood that secondary degenerative changes develop” following concussion. They termed this condition “traumatic encephalitis”.

A year later, Martland made the link between sport and long-term brain damage. He coined the term “punch drunk” in relation to boxers, observing symptoms such as mental confusion, tremors, and unsteadiness. He noted that this condition:

most often affects fighters of the slugging type, who are usually poor boxers and who take considerable head punishment, seeking only to land a knockout blow. It is also common in second-rate fighters used for training purposes, who may be knocked down several times a day.

These observations led Martland to conclude:

I am of the opinion that in punch drunk there is a very definite brain injury due to single or repeated blows on the head or jaw which cause multiple concussion hemorrhages in the deeper portions of the cerebrum.

Thus, from 1928, there was already a suggestion that concussive and perhaps sub-concussive blows could cause long-term neurological damage. Notably, he warned that this “condition can no longer be ignored by the medical profession or the public.”

The 1930s saw three papers published on the condition, including one by Millsbaugh, who referred to “dementia pugilistica” (i.e. dementia of the boxer). Each paper focused on the link between boxing and long-term neurological problems, but the issue did not receive as much attention as Martland had suggested it should. Perhaps because of the Second World War, it was not until the late 1940s that it reappeared in the literature.

3. CHRONIC TRAUMATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY

The term Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (“CTE”) was first used by Critchley in his 1949 paper on punch-drunk syndrome in boxers, but only in 1954 were the first anatomical findings of “dementia pugilistica” made in the brain of a deceased former boxer, who had presented with symptoms of Parkinsonism aged 38.

Later, Critchley wrote a second paper in which he noted that he had seen 69 cases of chronic neurological disease in boxers, which he described as “punch-drunkenness”. He considered that “in only a comparatively few cases does legitimate doubt occur about the possibility of there being some coincidental and non-related nervous or mental disease”. The symptoms he described bear a striking resemblance to those considered today to be symptoms of CTE:

gradual evolution of mental and physical anomalies marks the insidious onset of the encephalopathy. Among mental symptoms there is the slow appearance of a fatuous or euphoric dementia with emotional lability…Speech and thought become progressively slower. Memory deteriorates considerably…There may be mood-swings, intense irritability, and sometimes truculence leading to uninhibited violent behaviour…sometimes there is depression with a paranoid colouring.

Throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, the condition appeared several times in the literature internationally, referred to frequently as “boxer’s encephalopathy”, which included a further pathologically verified case. Then, in 1973, Corsellis et al. gave detailed descriptions of the various stages of CTE, based on the analysis of the brains of 15 deceased boxers in which they identified brain damage – “dementia pugilistica”. A year later, two further reports identified the disease in the brains of young boxers, post-mortem.

However, the literature up until that point had focused predominantly on the sport of boxing – as well as those who had served in the military and victims of domestic abuse. In 1975, Gronwall and Wrightson wrote in The Lancet of the “cumulative effect of concussion” in athletes, while a 1982 article stated that concussions cause “widespread microscopic changes” to the brain. It noted that “these abnormalities may evolve into gross atrophy after repeated injury.”

It is arguable, therefore, that from 1975 onwards, sports governing bodies should have been aware of the risks of long-term damage from repeated concussions and/or head trauma.

Certainly, from 1997, this seems to be an inevitable conclusion. In its summary statement on the management of concussion in sports, the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology wrote that:

Close observation and assessment of the injured athlete could be critical to the prevention of catastrophic brain injury and cumulative neuro-psychological deficits. Repeated concussions can cause cumulative brain injury in an individual injured over months or years…Frequently, the loss of objectivity on the part of the athletes, coaches, sports media, and spectators is an unfortunate and potentially harmful bias.

4. AMERICAN FOOTBALL & CTE

The 1990s saw a significant expansion in the scientific understanding of CTE, but it wasn’t until 2000 that the first scientific survey emerged suggesting that head trauma from American football “may lead to later neurological problems”.

Yet this was not the first form of football to discover CTE. In 1999, signs of CTE were found in the brain of a 23-year-old amateur soccer player, who regularly headed the ball and had suffered a single severe head injury. Studies dating back to 1989 have also linked heading the soccer ball to brain damage, while a coroner ruled in 2002 that former England footballer Jeff Astle had died from dementia brought on by repeatedly heading the ball.

In 2002, the First Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport, by the Concussion in Sports Group (“CISG”) made no specific mention of the long-term impact of concussion, other than that further research was needed.

Famously, in 2002, Dr Bennet Omalu discovered CTE in the brain of former NFL player, Mike Webster. Omalu’s findings were reported in the literature in 2005, with a second case confirmed a year later. In 2009, the NFL acknowledged that “it’s quite obvious from the medical research that’s been done that concussions can lead to long-term problems”. The NFL subsequently settled a class action lawsuit against it for its handling of concussion for up to $1billion.

Nonetheless, in the same year, the Third CISG Consensus Statement acknowledged the suggested association between sports concussions and late-life cognitive impairment, but no consensus was reached on the significance of the NFL findings. Still, it was agreed that clinicians “need to be mindful of the potential for long-term problems in the management of all athletes”.

By contrast, another research paper from 2009 suggested that:

by instituting and following proper guidelines for return to play after a concussion or mild traumatic brain injury, it is possible that the frequency of sports-related CTE could be dramatically reduced or perhaps, entirely prevented.

The first decade of the millennium thus appeared to (logically) confirm that CTE could be found in athletes outside of boxing, yet saw a reluctance in some quarters to accept that this could be so.

5. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

The past decade has seen further advancements in the understanding of CTE – though the science appears not to be universally agreed upon.

In 2011, it was observed that “one way to quickly and drastically reduce a sport’s concussion risk would be to limit unnecessary contact in practice”. Other suggestions included increased education for athletes and support staff, pre-participation examinations and good quality officiating. Yet this came more than 15 years after Mendez had previously suggested screening boxers with neuropsychological tests and neuroimaging to identify those at risk of CTE.

The 2013 CISG Consensus Statement accepted that CTE existed but found that a “cause and effect relationship” had not yet been demonstrated between CTE and concussions or exposure to contact sports. That conclusion was reiterated by the same group in 2017, albeit that it was then acknowledged that the “potential for developing [CTE] must be a consideration”.

However, it must be noted that the CISG Conferences are organised and sponsored by international sports federations, which raises the spectre that the relevant bodies may be constrained by potential conflicts of interest.

In any case, several independent papers have continued to demonstrate a link between repetitive head trauma and CTE, and thus a link between contact sports and CTE. This included the finding in a 2017 study that 99% of the NFL players whose brains were studied had CTE.

The condition has also been diagnosed in rugby players. Former Australian rugby union player, Barry Taylor was posthumously diagnosed with CTE in 2013, while former Irish prop Kenny Nuzum was similarly diagnosed in 2014 after his death aged 57. A 2019 paper identified CTE in two former Australian rugby league players. It has also been found in the brains of former ice hockey players, professional wrestlers, an Australian rules football player and a professional baseball player.

Notably, CTE has also been diagnosed in the brains of former soccer players, including that of Hilderaldo Bellini, who was part of the Brazilian World Cup-winning teams of 1958 and 1962 alongside Pelé. Dementia has also been shown to be three and a half times more common in retired soccer players than in the general population.

6. CONCLUSIONS

It is clear that scientists have been aware of the dangers of repeated head trauma in sport – to a greater or lesser degree – for the best part of a century. That awareness and understanding has evidently evolved considerably over time, though there is still no universal agreement on the precise nature of the relationship between contact sports and CTE, and other neurological conditions.

Nonetheless, the extensive literature on “dementia pugilistica” and the scientific advances from the 1980s onwards suggest that there are legitimate questions to be asked of governing bodies. Given the state of the scientific understanding, should they have done more to protect athletes, and should they have carried out or commissioned further research? It is difficult to think of a reason not to have done so.

Authored By

Ben Cisneros

Trainee Solicitor

Footnote

1. At present, CTE can only be diagnosed after death. However, it is possible to make a probable diagnosis in living people.

2. Glasgow Corporation v Muir [1943] 2 AC 448

3. Osnato M and Giliberti V: Postconcussion neurosis-traumatic encephalitis – a conception of postconcussion phenomena. Arch NeurPsych 1927, 18:181–214

4. Martland H: Punch drunk. JAMA 1928, 91:1103–1107

5. Parker HL: Traumatic encephalopathy (‘punch drunk’) of professional pugilists. J Neurol Psychopathol 1934, 15:20; Millsbaugh JA: Dementia pugilistica. US Naval Med Bulletin 1937, 35:297–361; Ravina A: Traumatic encephalitis or punch drunk. Presse Med 1937, 45:1362–1364

6. Critchley M: Punch-Drunk Syndromes: the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy of Boxers. Hommage a Clovis Vincent. Paris: Maloin; 1949.

7. Brandenburg W, Hallervorden J: Dementia pugilistica with anatomical findings. Virchows Arch 1954, 325:680–709

8. Critchley M: Medical aspects of boxing, particularly from a neurological standpoint. Br Med J 1957, 1:357–362

9. [9] Grahmann H, Ule G: [Diagnosis of chronic cerebral symptoms in boxers (dementia pugilistica & traumatic encephalopathy of boxers)]. Psychiatr Neurol 1957, 134:261–283; Neubuerger KT, Sinton DW, Denst J: Cerebral atrophy associated with boxing. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1959, 81:403–408; Serel M, Jaros O: The mechanisms of cerebral concussion in boxing and their consequences. World Neur 1962, 3:351–358; Mawdsley C, Ferguson FR: Neurological disease in boxers. Lancet 1963, 2:799–801; LACAVA G. BOXER'S ENCEPHALOPATHY. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1963 Jun-Sep;3:87-92

10. Courville CB: Punch drunk. Its pathogenesis and pathology on the basis of a verified case. Bull L A Neurol Soc 1962, 27:160–168.

11. Corsellis JA, Bruton CJ, Freeman-Browne D: The aftermath of boxing. Psychol Med 1973, 3:270–303

12. Hollnagel P. Punch drunk syndromet. Tre tilfaelde af kronisk encefalopati hos yngre boksere ["Punch-drunk" syndrome. Reports of 3 cases of chronic encephalopathy in young boxers]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1974 Dec 16;136(51):2871-4; Harvey PK, Davis JN. Traumatic encephalopathy in a young boxer. Lancet. 1974 Oct 19 2(7886):928-9.

13. The Lancet is one of the most reputable, widely read and cited medical journals. As such, this would have come to the attention of many doctors – not just specialists.

14. Gronwall D, Wrightson P. Cumulative effect of concussion. Lancet 1975;2:995-997

15. Hugenholtz H, Richard MT. Return to athletic competition following concussion. Can Med Assoc J 1982;127:827-829

16. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology, The management of concussion in sports (summary statement); Neurology 1997;48:581-585

17. See for example, Tokuda T et al. Re-examination of ex-boxers’ brains using immunohistochemistry with antibodies to amyloid beta-protein and tau protein. Acta Neuropathol 1991;82:280–85

18. American Academy Of Neurology. "Concussions May Spell Later Trouble For Football Players." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 5 May 2000.

19. Geddes JF, Vowles GH, Nicoll JA, Révész T: Neuronal cytoskeletal changes are an early consequence of repetitive head injury. Acta Neuropathol 1999, 98:171–178

20. See, Tysvaer, A.T., Storli, O.V. and Bachen, N.I. (1989), Soccer injuries to the brain. A neurologic and electroencephalographic study of former players. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 80: 151-156; Matser JT, Kessels AG, Jordan BD, et al. Chronic traumatic brain injury in professional soccer players. Neurology 1998;51:791–96; and Witol AD, Webbe FM. Soccer heading frequency predicts neuropsychological deficits. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003 May;18(4):397-417.

21. Aubry M, Cantu R, Dvorak J, et al. Summary and agreement statement of the first International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Vienna 2001 British Journal of Sports Medicine 2002;36:6-7.

22. The 2005 CISG Consensus was the same in this regard. See McCrory P, Johnston K, Meeuwisse W, et al Summary and agreement statement of the 2nd International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Prague 2004 British Journal of Sports Medicine 2005;39:196-204.

23. Omalu BI, DeKosky ST, Minster RL, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a National Football League player. Neurosurgery 2005;57:128–34

24. Omalu BI et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a national football league player: part II. Neurosurgery. 2006 Nov; 59(5):1086-92

25. N.F.L. Acknowledges Long-Term Concussion Effects, New York Time, 20 December 2009, Alan Schwarz

26. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K, et al. Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport: the 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2008 British Journal of Sports Medicine 2009;43:i76-i84.

27. McKee AC, et al: Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2009, 68:709–735.

28. McCrory P, Turner M, Murray J. A punch drunk jockey? Br J Sports Med 2004;38:e3; Omalu BI et al.: Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a professional American wrestler. J Forensic Nurs 2010, 6:130–136.

29. See for example Iverson GL, Gardner AJ, Shultz SR, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy neuropathology might not be inexorably progressive or unique to repetitive neurotrauma. Brain. 2019;142(12):3672-3693.

30. Daneshvar et al, The Epidemiology of Sport-Related Concussion, Clin Sports Med. 2011 Jan; 30(1): 1–17.

31. Ibid.

32. Mendez MF. The Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Boxing. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1995;25(3):249-262.

33. McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012 British Journal of Sports Medicine 2013;47:250-258.

34. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016 British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017;51:838-847.

35. The first CISG conference was organised by the IIHF, FIFA and the IOC. World Rugby has been actively involved in the CISG since 2008 and, for 2021, the CISG conference in Paris will be organised by the IOC and sponsored by FIFA, World Rugby, the FEI and the IIHF.

36. McKee AC. The Neuropathology of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: The Status of the Literature. Semin Neurol. 2020 Aug;40(4):359-369; McKee AC, Stein TD, Kiernan PT, Alvarez VE. The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain Pathol. 2015;25(3):350-364; McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy [published correction appears in Brain. 2013 Oct;136(Pt 10):e255]. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 1):43-64.

37. Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT, et al. Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football. JAMA. 2017;318(4):360–370

38. Buckland, M.E., Sy, J., Szentmariay, I. et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in two former Australian National Rugby League players. acta neuropathol commun 7, 97 (2019).

39. McKee AC, Daneshvar DH, Alvarez VE, Stein TD. The neuropathology of sport. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(1):29-51.

40. Ling, H., Morris, H.R., Neal, J.W. et al. Mixed pathologies including chronic traumatic encephalopathy account for dementia in retired association football (soccer) players. Acta Neuropathol 133, 337–352 (2017).

41. Nitrini R. Soccer (Football Association) and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A short review and recommendation. Dement Neuropsychol. 2017;11(3):218-220.