COVID-19 - Force majeure: Swiss law, CAS jurisprudence, and the jurisprudence of other sports tribunals

The COVID-19 outbreak has had a colossal impact on every aspect of life worldwide. Whilst the outbreak’s effects on the sporting world are clearly of secondary concern, it is nevertheless the case that enormous disruption has been, and will continue to be, caused to events in every country, in every sport, and at all levels.

Whether events are postponed (as in the case of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games), cancelled entirely (as in the case of Wimbledon) or prematurely concluded (as in the case of the Belgian Pro League), the scope for disputes is clear. That is particularly the case given that the situation faced is entirely novel (at least as regards the modern sporting world), such that it simply has not been legislated for.

Indeed, the degree to which existing rules and regulations will likely have to be ‘torn up’ is reflected by the FIFA guidelines “COVID-19 Football Regulatory Issues” published on 7 April 2020. Those guidelines call for players’ and coaches’ contracts to be automatically extended until the end of the delayed football season, propose guiding principles which (seemingly) would (in certain cases) allow parties to unilaterally vary employment contracts which “can no longer be performed”, and recommend allowing transfer windows to be altered to be in line with amended season dates. The scope for dispute arising from those guidelines is therefore both clear and significant.

Moreover, sports related disputes are likely to arise in relation to a huge variety of legal relationships, for example:

- Employer and employee;

- Funder and funded (e.g. a national governing body for an Olympic sport and an athlete);

- League and league member;

- International federation and federation member;

- Sponsor and sponsored;

- Broadcaster and rights holder;

- Ticket-holder and event organiser.

Many parties to such disputes will likely argue that they must be released from a contractual obligation on the basis that the COVID-19 outbreak represents a force majeure event.

Force majeure is, at root, a civil law concept. In many civil law jurisdictions, a force majeure clause will be treated as an implied term of a contract when an unforeseeable and unavoidable event that has not been caused by the negligence or fault of either of the parties has made performance impossible.

In this Tom Seamer (Barrister) provides a brief introduction to the doctrine of force majeure:

- under Swiss law;

- in the jurisprudence of the Court of Arbitration for Sport (the “CAS”); and

- in the jurisprudence of other sports tribunals.

Force majeure: Swiss law

The majority of major international sports federations are domiciled in Switzerland, with statutes and regulations that provide that – subsidiarily to their own rules and regulations – the law applicable to a dispute, or a particular type of dispute, will be Swiss law.

While it would typically not be necessary to resort to Swiss law, it is likely that, as regards disputes related to the COVID-19 outbreak, resort will frequently need to be made to Swiss law, as the applicable rules and regulations are unlikely to have legislated for situations such as the COVID-19 outbreak. The CAS case law discussed further below tends to confirm that hypothesis. Accordingly, many of the sports related disputes that will arise as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak will likely be determined by reference to Swiss law.

In addition, many of those disputes will be determined by the CAS, whether by the ordinary arbitration division or on appeal, and Swiss law is frequently applied by the CAS in resolving disputes.

However, strictly speaking, Swiss law does not recognise a general defence of force majeure.

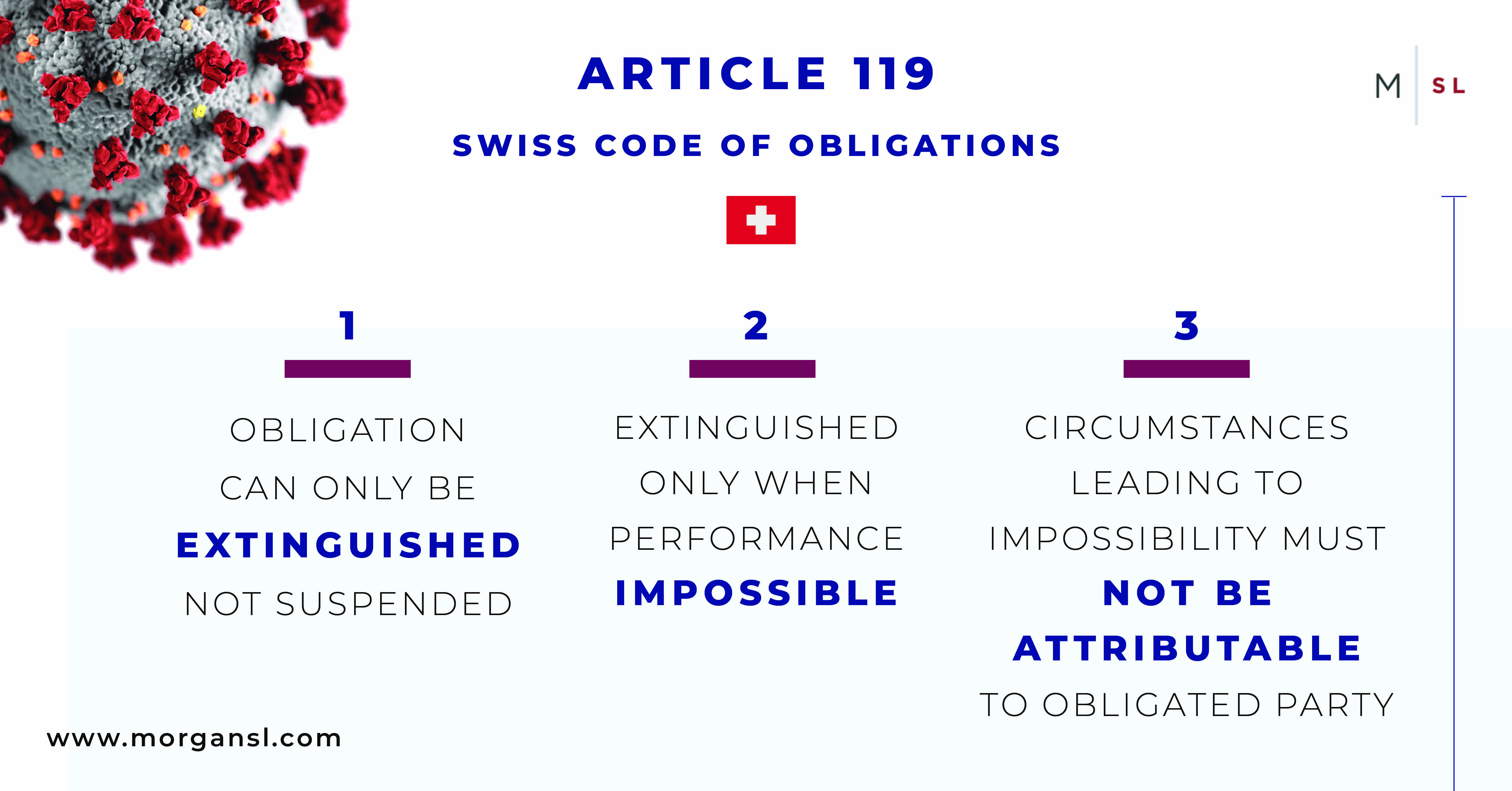

Nevertheless, Article 119 of the Swiss Code of Obligations (“SCO”) provides for a force majeure type defence, in stating that:

An obligation is deemed extinguished where its performance is made impossible by circumstances not attributable to the obligor…

Certain key conclusions can be drawn from the above:

- Article 119 SCO does not seem to allow for the suspension of an obligation (as opposed to its extinguishing) due to a force majeure type event;

- under Article 119 SCO, in order for an obligation to be deemed extinguished, its performance needs to be impossible; and

- under Article 119 SCO, the circumstances leading to such impossibility must not be attributable to the obligated party.

Whilst a defence based on Article 119 SCO is possible, the jurisprudence of the Swiss Federal Tribunal (the “SFT”) makes clear that, unsurprisingly, such a defence will not easily be made out.

Thus, and for example, in its decision 111 II 352, the SFT had to decide whether a contractor could escape its contractual obligations to construct a nuclear energy plant because the Swiss Federal Council had suddenly instituted an export embargo which made it impossible for the contractor to comply with its obligations.

Whilst the SFT accepted that, due to the embargo, the contractor was unable to meet its contractual obligations, the defence based on Article 119 SCO was nevertheless rejected. That was because the SFT held that, as a company active in the field of nuclear energy, the contractor should have recognised that such an embargo could be suddenly instituted.

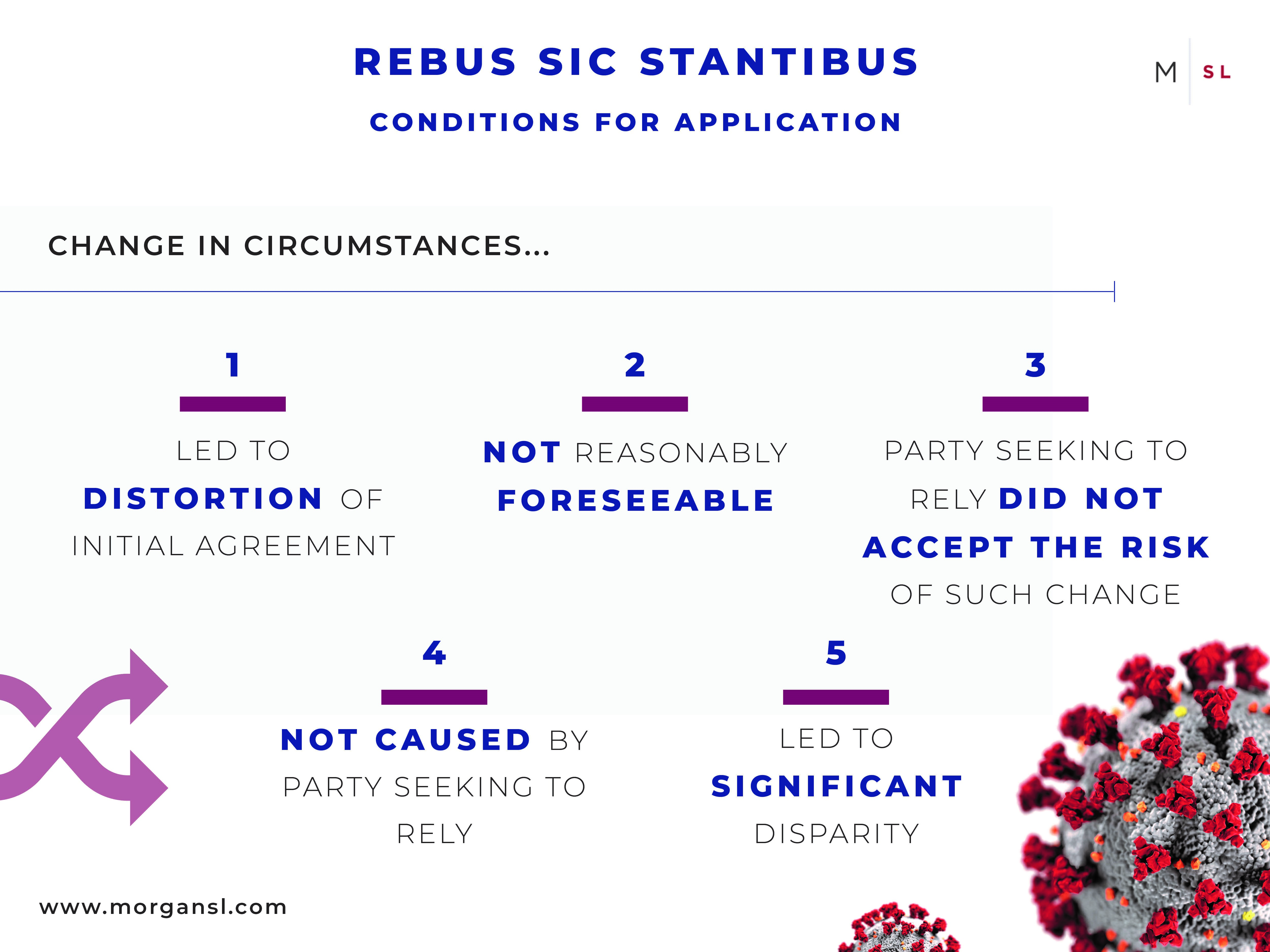

In addition to Article 119 SCO, Swiss jurisprudence has recognised that sometimes there may be a change of circumstances (from those that existed when the contract was entered into) that is so radical as to substantially alter the equilibrium of the contract. In extreme cases it may be unfair, and contrary to the principle of good faith, to insist on the performance of the original terms of the contract. In such cases Swiss jurisprudence has recognised and developed the doctrine of rebus sic stantibus.

The doctrine of rebus sic stantibus provides a party with a right to be discharged from an obligation (or even all of its obligations) under a contract when extraordinary and unforeseeable events have occurred which mean that performance of those obligations cannot be expected by virtue of good faith.

Typically, the following conditions must be met for the doctrine of rebus sic stantibus to apply:

- a change in circumstances must have occurred that has led to a fundamental distortion of the initial agreement;

- the change in circumstances must not have been reasonably foreseeable;

- the party seeking to rely on the doctrine must not have accepted the risk of such a change (implicitly or explicitly) at the time of making the contract;

- the change in circumstances must not have been caused by the party which seeks to rely on the doctrine; and

- the change in circumstances must have led to a significant disparity between the parties’ obligations.

Just as with Article 119 SCO, the case law of the SFT makes clear that a stringent test is to be applied when determining whether a contract can be terminated or modified on the basis of the doctrine of rebus sic stantibus. By way of example, in its decision 122 III 97, the SFT held that:

…The clausula rebus sic stantibus… very rarely leads to a judicial dissolution or adjustment of the contract, according to the practice of the Swiss Federal Tribunal (…) Such a solution is only affirmed if the relationship between performance and consideration is disturbed as a result of an extraordinary and unforeseeable change in circumstances in such a way that the creditor's insistence on his contractual claim constitutes a downright usurious exploitation of the disproportion and thus a manifest abuse of rights.

(Unofficial translation)

Force majeure: CAS jurisprudence

From the publicly available jurisprudence, it appears that CAS has historically taken a civil law approach when faced with force majeure arguments. That is to say that CAS has previously considered the principle of force majeure to be of potential application notwithstanding the (seeming) lack of any force majeure clause within the relevant contract.

Thus, in CAS 2018/A/5779 Zamalek Sporting Club v. FIFA the panel considered a force majeure argument without having cited any clause in the contract, and having held that:

58. …the legal concept of force majeure is widely and internationally accepted and, in particular, is valid and applicable under Swiss law…

Further, the panel was clear that the principle of force majeure is “well-established” at CAS and noted that CAS jurisprudence states that:

60. …force majeure implies an objective (rather than a personal) impediment, beyond the control of the “obliged party”, that is unforeseeable, that cannot be resisted, and that renders the performance of the obligation impossible…

However, it is equally clear that the CAS has historically applied a stringent test when determining whether an event constituted force majeure. Indeed, the following comment of the sole arbitrator in CAS 2006/A/1110 PAOK FC v. UEFA is often cited:

17. …the conditions for the occurrence of force majeure are to be narrowly interpreted, since force majeure introduces an exception to the binding force of an obligation.

In accordance with those remarks, CAS panels have rejected force majeure arguments made on each of the following grounds:

- a difficult financial and sporting situation (asserted justification for non-payment);

- the club’s relegation to a lower division (asserted justification for non-payment);

- the sudden resignation of a number of a club’s office-holders which, it was argued, created “political turmoil” (asserted justification for non-payment);

- the failure to secure a bank guarantee (asserted justification for non-payment);

- the alleged illegal blockage of bank accounts (asserted justification for non-payment);

- a “disease spreading among the team’s players” (asserted justification for the team’s non-appearance at a match); and

- the Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016 (which led the Royal Moroccan Federation of Football to attempt to postpone the 2015 African Cup of Nations).

Indeed, at least based on publicly available materials and to the authors’ knowledge, a force majeure argument has only succeeded at CAS on one occasion, being CAS 2014/A/3463 & 3464 Alexandria Union Club v. Sánchez & Cazorla.

That case concerned an employment dispute between an Egyptian football club and two football coaches. Due to circumstances related to political events in Egypt, the 2012/2013 Egyptian football season was terminated in April 2013 and the results of the Egyptian League were cancelled. The coaches unilaterally terminated their employment contracts.

In dealing with the consequences of that unilateral termination, the sole arbitrator held that:

80. …the Egyptian civil war is an event of force majeure, which is beyond the Parties’ control, which the Parties could not have reasonably provided against before entering into the contract, which could not reasonably have been avoided or overcome, and which is not attributable to any of the Parties. Under these circumstances, the Sole Arbitrator finds that the events which put an end to the 2012/2013 season, and which admittedly occurred on 1 April 2013, prevented the Appellant from performing all or part of its contractual obligations. As a result, and as of 1 April 2013, the Appellant must be released from further performance of the obligations concerned.

Thus, based on publicly available materials and to the authors’ knowledge, an argument of force majeure has only previously succeeded at CAS as a result of the outbreak of (what the sole arbitrator termed) a civil war. It is therefore clear that (consistent with the approach of the SFT) the cited intervening circumstances will have to be extreme if a force majeure argument is to succeed at CAS.

Force majeure: other sports tribunals

Of course, whilst CAS jurisprudence is of critical importance, the CAS is not the only sports specific arbitral tribunal.

Indeed, the FIFA decision-making bodies consider hundreds of disputes each year. Thus, unsurprisingly, they have on occasion been required to consider force majeure arguments.

In that regard it should be noted that, similarly to the CAS, the FIFA decision-making bodies have previously taken a civil law approach to the principle of force majeure, and have therefore considered the principle of force majeure to be of potential application notwithstanding the lack of any force majeure clause within the relevant contract.

Historically, and again similarly to the CAS, the FIFA decision-making bodies have stressed that a force majeure will only rarely succeed. Thus, in I v. Club B (2016) the FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber (the “DRC”) rejected the club’s argument that the annulment of a league by the national federation amounted to a force majeure event such as to release it from its obligations to the player.

In so doing, the DRC held that the principle of force majeure is generally (only) applicable to:

…unpredictable situations, facts or circumstances that are extraordinary and unexpected.

Indeed, the authors are unaware of any award of a FIFA decision-making body in which a force majeure argument has succeeded.

Notwithstanding the previous reluctance of the FIFA decision-making bodies to hold a force majeure defence successful, on 7 April 2020 the Bureau of the FIFA Council declared that (as regards the status and transfer of players):

…The COVID-19 situation is, per se, a case of force majeure for FIFA and football.

That declaration was made in accordance with Article 27 of the FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players, which provides that:

…cases of force majeure shall be decided by the FIFA Council whose decisions are final.

Interestingly, neither that provision nor its predecessors had been utilised previously, notwithstanding that force majeure arguments have previously been made before the FIFA decision-making bodies.

In any event, in utilising that provision, FIFA no doubt seeks to reduce the scope for dispute as to whether the COVID-19 outbreak’s impact on a particular contractual arrangement does, or does not, amount to a force majeure event.

However, whilst Article 27 is clear that the decisions of the FIFA Council are final in that regard, it will be interesting to see if the FIFA Council’s declaration will be treated as being of universal application. To posit a purposefully extreme example, would a Belarussian club succeed in an argument that the COVID-19 outbreak represents a force majeure event on the basis of the FIFA Council’s declaration, notwithstanding that football in Belarus continues as normal?

Finally, it must be remembered that the FIFA Council’s declaration under Article 27 is only applicable as regards disputes concerning the status and transfer of players.

The Basketball Arbitral Tribunal (the “BAT”) is another well-established sports tribunal. Notably, a force majeure defence was (at least in part) accepted in BAT 0529/14 Feghali v. Cercle Sportif Maristes, which concerned an employment dispute between a player and a club.

In that case the sole arbitrator held that the suspension of the Lebanese basketball league amounted to a force majeure event:

44. …the Club has established the existence of a type of force majeure having disrupted and negatively affected its organization and activities during at least the first half of the 2013-2014 season (…) since the Club had no responsibility for and no control over the postponement of the Lebanese first division basketball championship during that period. Furthermore, that disruption will necessarily have complicated the Club’s financial situation due to absence of official games and the requirements of sponsors.

However, in deciding the case ex aequo et bono, the sole arbitrator held that the existence of the said force majeure event did not serve to terminate the club’s obligations under the employment contract, but instead served to reduce the damages that would have otherwise been payable to the player.

Conclusions

Thus, to summarise:

- Swiss law recognises the possibility of a force majeure type defence (whether by virtue of Article 119 of the Swiss Code of Obligations or the doctrine of rebus sic stantibus);

- The CAS and other sports tribunals also recognise the principle of force majeure (and have on occasion deemed such a defence to be made out);

- However, parties can expect that the test that will be applied in determining whether such a defence is made out will be a stringent one.

While it may seem difficult to characterise the COVID-19 pandemic as anything but a force majeure event, the extent to which a party can claim relief on the basis of a force majeure type argument will inevitably depend on the particularities of each case – for instance:

- the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the relevant region and sport;

- the economic situation of the relevant parties;

- the proportionality of any adjustment given the financial relationship of the parties;

- the manner in which any such adjustments were made (i.e. with or without warning, negotiation, consultation etc); and

- whether parties in equivalent positions (e.g. all of the players at a club) have been treated equally.

Accordingly, there is likely enough to encourage a party to a sports law dispute which is subject to Swiss law or before a sports tribunal (such as the CAS) to make a force majeure argument, but there is also likely enough to encourage the corresponding party to dispute or, at least to seek to mitigate, the point.

All in all, it is difficult to see how a flood of litigation will be avoided given the COVID-19 outbreak’s massive impact on the sporting world.

Footnote

1. ‘Superior force’

2. In addition, some contracts (in both common and civil law jurisdictions) contain force majeure clauses which will define (or at least should have defined) what amounts to a force majeure event for the purposes of that contract. This article does not address situations in which the contract contains such a force majeure clause.

3. Mario worked at FIFA for almost 6 years overseeing over 500 cases heard by the FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber and the Players’ Status Committee. Mario also acted on behalf of FIFA before the Court of Arbitration for Sport on numerous occasions.

4. Tom’s practice focuses on contentious doping matters and civil claims arising from doping disputes. He represents clients across a range of sports and jurisdictions, particularly before the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

5. See, for instance, Article 57(2) of the FIFA Statutes and Article 64 of the UEFA Statutes

6. See Article R45 of the CAS Code (as regards Ordinary Arbitration procedures) and Article R58 of the CAS Code (as regards Appeal procedures – and noting again that the majority of major international sports federations are domiciled in Switzerland)

7. ‘Things thus standing’

8. See SFT decisions BGE 93 II 185 and BGE 101 II 17

9. See SFT decisions BGE 135 I 1 and 4A_375/2010

10. With further references to the SFT decisions BGE 100 II 345 and BGE 107 II 343

11. In that regard, see also CAS 2006/A/1110 PAOK FC v. UEFA

12. As to which, see the research of the authors below.

13. CAS 2014/A/3533 Football Club Metallurg v. UEFA

14. CAS 2016/A/4692 Kardemir KD v. UEFA

15. CAS 2016/A/4874 Club Africain v. Seidu Salifu

16. CAS 2010/A/2144 Real Betis Balompié SAD v. PSV Eindhoven

17. CAS 2015/A/3909 Club Atlético Mineiro v. FC Dynamo Kyiv

18. CAS 2007/A/1264 FC Karpaty v. Football Federation of Ukraine & FC Metalist Kharkiv

19. CAS Bulletin 2016/1 at page 76

20. There may be other CAS cases that deal with force majeure arguments as not all CAS awards are made public.

21. See for example the decision of the FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber in I v. Club B (2016) at paragraph 8 (at section 1) and paragraphs 17-20 (at section II)

22. Albeit, with respect to the parties in question, the factual bases on which such arguments have previously been run have, for the most part, been relatively weak.

23. See page 2 of the FIFA guidelines “COVID-19 Football Regulatory Issues”

24. The BAT’s willingness to consider force majeure arguments has been seemingly further confirmed by the International Basketball Federation’s (FIBA) Circular Letter no. 24 dated 23 March 2020, which informed member associations that: …in case of financial disputes arising from contracts including a BAT clause, it will be for the BAT as an independent tribunal to decide (…) FIBA has been informed by the BAT that the first case(s) involving COVID-19 as “force majeure” will be treated in an expedited manner and will be published with their reasoning on the FIBA website, so as to provide as early as possible relevant guidance to the actors in professional basketball”.

25. As required by the BAT Rules

26. Particularly given FIFA’s recognition that the COVID-19 outbreak is a force majeure event (at least in the context of the contractual arrangements and transfers of players).

27. Albeit disputing that COVID-19 constitutes a force majeure event is likely to be much more difficult in disputes concerning the contractual arrangements and transfers of football players given that the FIFA Council has declared that in those contexts, the COVID-19 outbreak does amount to a force majeure event (as explained above).