The Basketball Arbitral Tribunal Part 1 (of 3) - An Introduction

Peter Sibley, a paralegal at Morgan Sports Law, examines the Basketball Arbitral Tribunal and the decision making process adopted by its arbitrators in deciding disputes ex aequo et bono. This is the first article in a three part series on the Tribunal and its jurisprudence.

“Jarndyce and Jarndyce drones on. This scarecrow of a suit has, in course of time, become so complicated that no man alive knows what it means…” These famous words describe the monotony of legal disputes and the often-significant expense in time and money involved in fighting them.

In England and Wales this has, inter alia, driven the recent focus in litigation on procedural proportionality. This means the procedural rules are designed to deliver justice at proportionate, rather than at any, cost. In Switzerland, in the discrete area of basketball-related contractual disputes, proportionality has been taken one step further and applied to the design of substantive legal rules.

In the face of a significant practice “whereby both [basketball] clubs and players failed to respect the contracts that they had signed” and in which “breaches of contract in international basketball often went unsanctioned and the injured party had to spend years fighting for its rights at great financial expense in an unfamiliar legal system”,the Basketball Arbitral Tribunal ( “BAT”) was set up. The BAT was set up upon the initiative of, and is an officially recognized organization of, the global governing body of basketball, the Federation International Basketball Association (“FIBA”).

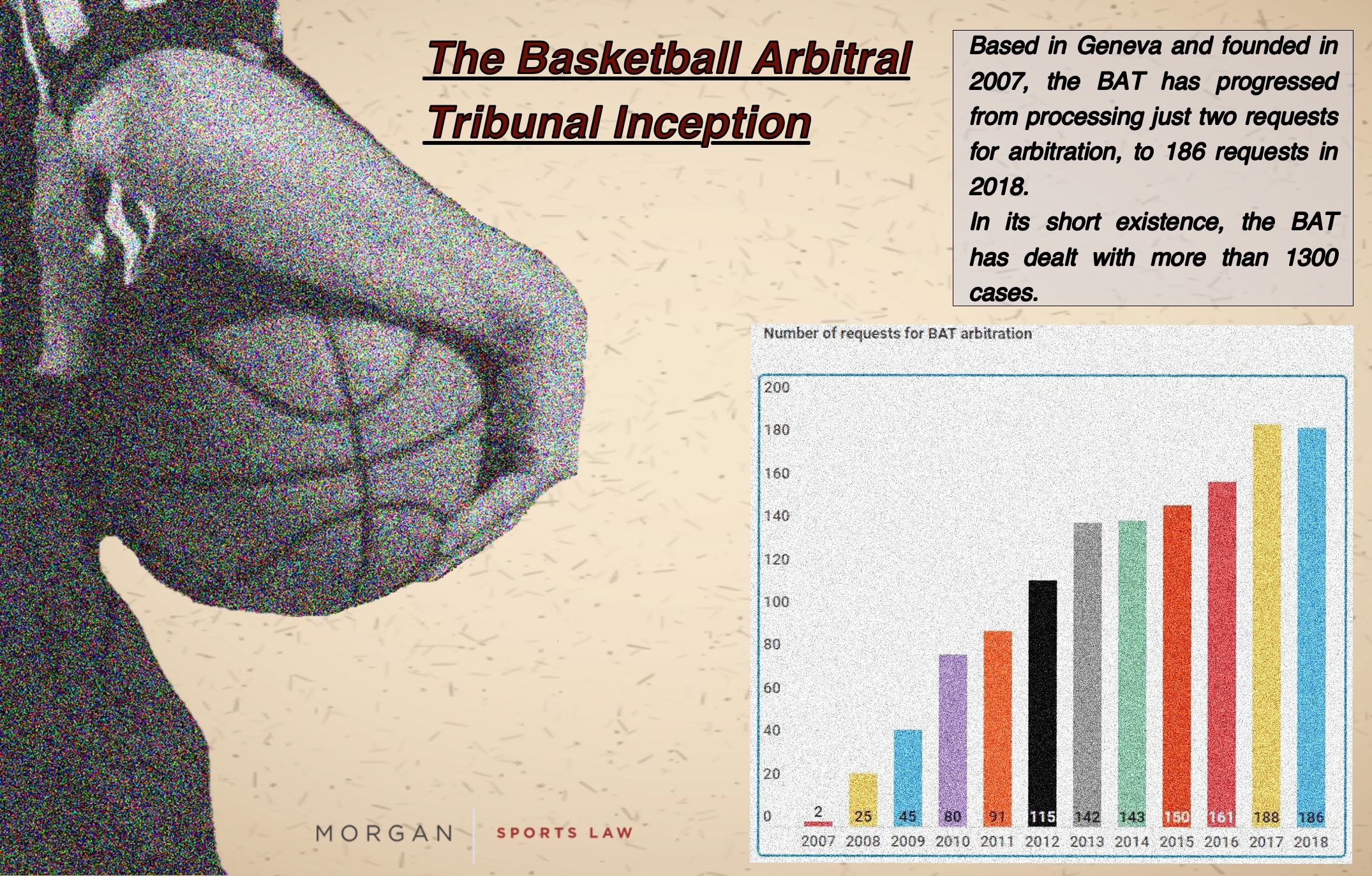

The BAT is an independent court of arbitration under Swiss Law and is governed by Chapter 12 of the Swiss Act on Private International Law (“PILA”). The BAT’s seat is Geneva, Switzerland. It has quickly progressed, since its inception in 2007, from processing just two requests for arbitration, to 186 requests in 2018. In its short existence it has dealt with more than 1300 cases. The BAT primarily deals with contractual disputes. Breaches of FIBA rules and the imposition of sanctions, including anti-doping matters, are dealt with by the FIBA Disciplinary Panel.

The BAT is currently comprised of 8 highly experienced arbitrators. A ‘core feature’ of the BAT is that each dispute is dealt with by a sole arbitrator. Disputes are fought via written submissions unless the Arbitrator decides a hearing is needed. Reasoned awards are not provided in disputes involving less than 100,000 Euros, although one may be requested.

The guiding principles in the BAT’s inception were efficiency and proportionality. This is reflected in its procedural and substantive rules. One of the unique features of the BAT is the application of ex aequo et bono as the applicable substantive law.

This means the arbitrator decides the matter in accordance with “general considerations of justice and fairness without reference to any particular national or international law”. The main benefit of ex aequo et bono is efficiency and proportionality, by avoiding the expense involved in navigating intricate and unfamiliar law inevitably involved in international contractual disputes. The main potential drawback is ‘the lack of predictability’. The source of this is the fact that such a decision maker ‘while deciding a particular dispute may be guided merely by what he [or she] deems just and equitable.’ Resolution of disputes in this way could amount to ‘virtually an abandonment of the notion of a "substantive law" of the contract altogether.’

However, as will be explored in part 2 of this series, when ex aequo et bono is applied as the applicable law it is usually subject to limits so as to reduce the unpredictability the application of the principle could entail. Furthermore, on examination of the jurisprudence and rules of the BAT, beneath the surface of ex aequo et bono decision making, there lies a carefully balanced decision-making process. This process strikes the balance between efficiency and predictability.

(i) The sole deciding arbitrator will analyse the contractual arrangements between the parties and will give significant weight to these. The legal principle of pacta sunt servanda, which provides that ‘parties who make a bargain are expected to stick to that bargain’, is applicable in ex aequo et bono arbitration before the BAT and is an ‘overriding consideration.’

(ii) Only then will the sole arbitrator consider equitable modification of the contractual position, ex aequo et bono, in accordance with established instances of such modification. This involves the controlled application of “considerations of justice and fairness which may not be imminently rooted in the contractual language.” These established instances will be explored in more detail in part 3 of this series. These established instances have been developed such that if they apply, the outcome “would be no different than the outcome under a national law in the vast majority of cases.”

In respect of (i) and (ii), the architects of the BAT state, ‘the arbitrator applies the contractual provisions unless this is grossly unfair.’This is reinforced by the BAT itself in award 0756/15, ‘parties should not seize on a literal translation of the phrase ex aequo et bono and consider that “justice” and “equity” provide them with a route to unprincipled and unmoored indulgence for poor contractual choices’ and by the CAS in BC VEF Riga v. Kaspars Berzins et al, ‘Even if a panel decides ex aequo et bono it may normally not derogate from the wording of a contract.’

(iii) Finally, the points raised by a particular dispute will be considered by the BAT president, and potentially by arbitrators other than the sole deciding arbitrator, to ensure consistency. Article 16.1 of the BAT Arbitration Rules provides that the sole deciding BAT arbitrator must send the award (before it is finalised and signed) to the BAT President who, ‘in the interest of the development of consistent BAT case law’ may make suggestions and or consult with other BAT arbitrators on issues of principle raised by the award.

Predictability thus comes from (i) anchoring the decision-making process to the contractual position; (ii) modification in accordance with established instances; and (iii) Article 16.1 of the BAT Arbitration Rules. Efficiency, on the other hand, comes from the modification of the contractual position in accordance with ex aequo et bono, if an established instance applies, as opposed to with a particular national or international law.

This carefully balanced scheme maintains efficiency without unduly undermining predictability in ex aequo et bono decision making in the BAT.

Footnote

1. The author would like to thank Mike Morgan of Morgan Sports Law and Dr Heiner Kahlert of Martens Rechtsanwälte for their thoughtful and thorough review of prior drafts of this article.

2. Charles Dickens, Bleak House

3. https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/law-society-magna-carta-lecture.pdf

4. D. Martens, The Basketball Arbitral Tribunal (BAT) and its commercial brother (2016) ISLR 43, pg 43

5. http://martens-lawyers.com/en/basketball-arbitral-tribunal-en/

6. FIBA General Statutes, article 33.1 https://fiba3x3.com/docs/fiba-general-statutes-2017.pdf

7. FIBA Internal Regulations, Book 3, Chapter 10, [331] http://www.fiba.basketball/internal-regulations/book3/players-and-officials.pdf

8. BAT Arbitration Rules, 2 http://www.fiba.basketball/bat/process/arbitration-rules-january-1-2017; Chapter 12 sets out applicable procedural mechanisms concerning, inter alia, challenge of arbitrators and the enforcement of BAT awards under the New York Convention https://www.swissarbitration.org/files/34/Swiss%20International%20Arbitration%20Law/IPRG_english.pdf

9. FIBA Internal Regulations, Book 3, Chapter 10, [330] (see footnote 7)

10. http://www.fiba.basketball/en/Module/c9dad82f-01af-45e0-bb85-ee4cf50235b4/984a5df1-a490-49a5-8aa4-86d985e703d9

11. See footnote 5

12. FIBA Internal Regulation, Book 3, Chapter 10, [326] (see footnote 7)

13. FIBA Internal Regulations, Book 4 Anti-Doping, article 8.1.1 http://www.fiba.basketball/internal-regulations/book4/anti-doping.pdf; Book 1 General Provisions, Chapter 6, [152] https://www.fiba.basketball/internal-regulations/book1/general-provisions.pdf

14. http://www.fiba.basketball/bat/composition.pdf

15. BAT AR, 8.1 (see footnote 8)

16. BAT AR, 13.1 (see footnote 8)

17. BAT AR, 16.2 (see footnote 8)

18. BAT Arbitration Rules, Pre-amble 0.1 and 0.2 (see footnote 8); see footnote 5; FIBA Internal Regulations, Book 3, Chapter 10, [324] (see footnote 7)

19. Examples of this include short time limits and the making of submissions generally in writing only.

20. BAT AR, 15.1 and preamble 0.2 and 0.3 (see footnote 8)

21. Ibid. All BAT cases cited in this article apply ex aequo et bono as the applicable law.

22. See footnote 4, pg 44

23. https://www.law.muni.cz/sborniky/cofola2008/files/pdf/mps/herboczkova_jana.pdf

24. M. Parish, The proper law of an arbitration agreement (2010) Arbitration 661, pg 676

25. BAT 0756/15, [58] to [62] http://www.fiba.basketball/en/Module/85132837-66aa-4ff3-a063-8cdfe44ea14d/ba7835a7-5e83-40b8-a9c8-378a478aa797

26. Ibid, [39]

27. BAT 1158/18, [29] http://www.fiba.basketball/en/Module/85132837-66aa-4ff3-a063-8cdfe44ea14d/50a89343-d03a-4a12-8367-0d7df0d5ebf4

28. E. Hasler, The Basketball Arbitral Tribunal – An Overview of Its Process and Decisions (2016) http://lk-k.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/YISA_2015-Chapter_6_Hasler-Levy-Kaufmann-Kohler-Basketball-Arbitral-Tribunal.pdf

29. See footnote 27

30. See footnote 4, pg 45

31. See footnote 5

32. See footnote 25, [59].

33. CAS 2014/A/3524, [67] https://jurisprudence.tas-cas.org/Shared%20Documents/3524.pdf

34. See footnote 8, 16.1.

35. See footnote 32